Electronic Music in the Arab world 1

Part I: How did electronic music start?

Introduction

This series of articles explores the history, styles, and uses of electronic music in the Arab world, focusing on the technological advancements that have contributed to its emergence and its prominent applications in music composition and performance. Additionally, these articles shed light on the presence of electronic music in radio, television, cinema, and live performances in the Arab world, reviewing the works of composers who have incorporated electronic music into their compositions. Covering the period from the beginnings of electronic music in the 20th century to the present day, the first article provides an overview of the early days of electronic music, its incorporation into various musical styles, and includes musical examples and discussions.

In the Beginning Was the Electricity

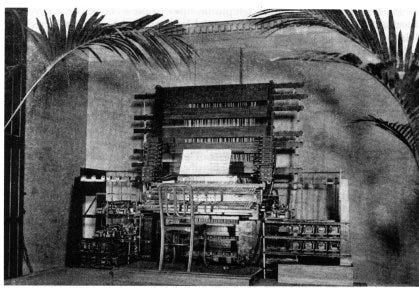

Since the invention and spread of the telephone around 1850, and later the radio around 1920, humans have attempted to transmit music via telephone wires or radio waves. Several scientists also developed machines capable of producing sound through electricity. Although the early history of electronic music requires further research, the first widely recognized instrument was the Telharmonium, invented by Thaddeus Cahill in 1896.

This massive instrument, weighing several tons, was the first electric device used to produce music broadcast directly through telephone wires in 1905 in New York City. Hotel and bar owners sought this less expensive music broadcasting service to replace the need for numerous musicians.

The second and perhaps more famous instrument was the Theremin, invented by Russian Leon Theremin in 1928. While the Telharmonium weighed several tons and featured a piano or organ-like keyboard, the Theremin embodied the spirit of the radio broadcast era and science fiction. The player does not touch the instrument but moves their hands in the air near two antennas, altering the pitch with one hand and the volume with the other.

Subsequent electronic instruments included the electric piano in 1931, the electric guitar in 1932, and the electric organ in 1935. Although composers sought new sounds, the nature of music composition and the aesthetics of musical material were initially not significantly impacted by these instruments. Many composers wrote traditional pieces or roles for these instruments or used them to play classical pieces. However, a new wave of inventions would forever change the aesthetics of music and composers' perceptions of sound.

Electronic Recording Technologies That Changed Music

The history of recording devices dates back to 1877 when Thomas Edison invented the phonograph, which recorded sound by etching grooves on cylinders or discs using sound vibrations. Electronic recording devices emerged around 1925, allowing longer and more accurate recordings. Soon, these recording devices themselves became musical instruments. In 1939, John Cage composed "Imaginary Landscape No.1" for two record players, a piano, and a Chinese cymbal.

In Cage's piece, two performers control the record players, allowing the pitch of the sounds to be altered, thereby using the record players as musical instruments. This limited use of recording devices would not last long, as new recording and sound production techniques would radically change traditional composition and performance methods.

The widespread adoption of magnetic tape in the 1940s allowed for sound modification, amplification, transformation, repetition, and frequency changes. This shift directly led to two new directions in music composition: Musique Concrète in France in 1948 by Pierre Schaeffer and Elektronische Musik in Germany in 1953 by Karlheinz Stockhausen.

However, the Egyptian composer Halim El-Dabh preceded these European pioneers. In 1944, he composed what is considered the first piece of electronic music titled "The Expression of Zaar."

El-Dabh created his piece by manipulating recorded sound from a Zaar ritual, a traditional ceremony involving music and singing performed by women to expel evil spirits. He borrowed a recording device from Middle East Radio (Radio Cairo) and worked on his composition in one of its studios. Musicologist Varese Bradley noted that El-Dabh re-recorded the sound material on magnetic tape, altering the speed, electrical current intensity, and recording room echo by changing the position of movable walls in the studio to achieve the desired sound. El-Dabh presented the recording in a 1944 art exhibition in Cairo.

In subsequent years, El-Dabh's contemporaries from the Musique Concrète school in France and Europe recorded everyday sounds, noises, and nature sounds and remixed them. Pierre Schaeffer, one of the pioneers of this school, mixed recordings of train sounds to create his piece "Etude aux chemins de fer" in 1948.

Other composers sought to integrate this composition technique with orchestral instruments. One such composer was Edgard Varèse, who composed "Déserts" for a group of wind instruments, percussion, and a recording device that played a pre-prepared tape.

On the other hand, the Elektronische Musik school in Germany relied solely on pure electronic sounds. One of the early examples of this school is Karlheinz Stockhausen's "Studie I" in 1953.

During the same period, numerous recording studios emerged, collaborating with a new generation of composers enthusiastic about this new music in the United States, Australia, Japan, and later in the 1960s in the Soviet Union.

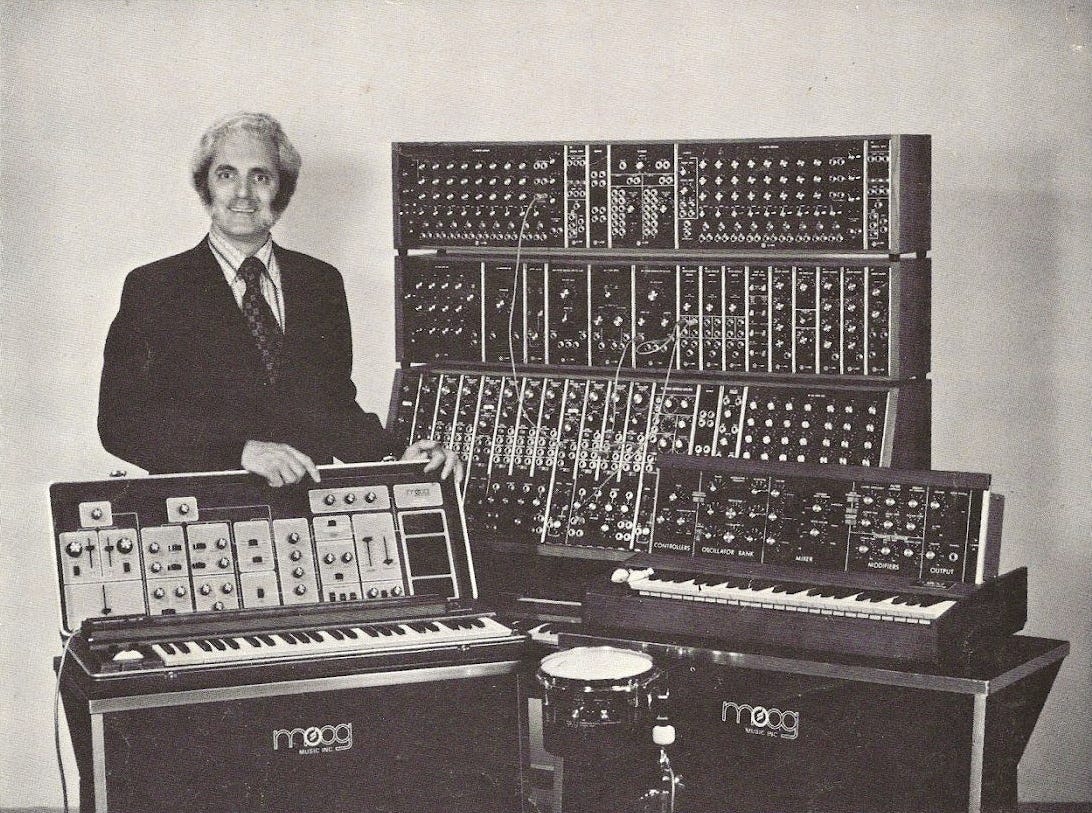

In 1964, Robert Moog developed the first modern synthesizer capable of producing, filtering, manipulating sounds, and playing sequences automatically.

The synthesizer's rich sounds and relative ease of play, due to its piano-like keyboard, contributed to its widespread use in popular music.

The release of the album "Switched-On Bach" by American synthesizer player Wendy Carlos significantly promoted the new instrument's sound through Bach's melodies, who had been dead for over 200 years. The adoption of the synthesizer by many musicians led to new genres in the 1970s, such as Progressive Rock, Ambient Dub, and Synth-pop. In the 1980s, Electronic Dance Music (EDM) emerged with new genres like House, Techno, and Trance, accompanied by the rise of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) festivals.

The widespread availability of personal computers and home recording studios in the 1990s allowed the emergence of Indie Electronic music. Computer programs, continually evolving since the 1980s, led to the development of the MIDI system, which enables computers to communicate with electronic musical instruments. By the 21st century, musicians shifted from using traditional musical instruments like synthesizers to computer programs that could simulate these instruments.

Electronic Instruments and Music in the Arab World

Electronic instruments entered the Arab music scene well before the 21st century, starting in the 1970s. Cairo, having a history of engaging with Western music, established the first opera house in the region in 1871. In the 1970s, songs played in bars and nightclubs had a Western influence, including rock, pop, and jazz. Guitarist Omar Khorshid significantly contributed to playing Arabic music on electronic instruments like the electric guitar and synthesizer, as evidenced by his 1974 album "Rhythms from the Orient."

Khorshid presented several classic Arabic songs as instrumental music arranged for electric guitar and synthesizer, bringing the sound of these instruments closer to the Arab ear through familiar melodies. Egyptian Magdi El-Husseini was one of the pioneers of playing the electric organ in the Arab world.

The electric organ was first used in Arabic music in 1969 in Umm Kulthum's song "Aqbal al-Layl" (the night has come) composed by Riad Al-Sunbati. The organ's use was consistent with the aesthetics of Arabic music, playing a dramatic melody in the song's introduction and then engaging in a simple dialogue with the string section.

The electric organ was also used in Abdel Halim Hafez's song "Qari'at Al-Finjan" (coffee fortune teller) composed by Mohamed Al-Mougy in 1976. The organ opens the song with mysterious sounds and engages in a short dialogue with the string section before returning to play a traditional melody consistent with the aesthetics of Arabic music. The organ's mysterious sounds reappear before the singing starts, suggesting the magic and fortune-telling atmosphere experienced by the protagonist of "Qari'at Al-Finjan."

The Spread of Electronic Instruments

The electronic keyboard, a synthesizer capable of simulating pre-programmed instrument sounds and playing various rhythms, became widespread in the 1980s. Some models could even perform the quarter tones used in many Arabic maqamat (musical modes). In 1986, Yamaha released the first electronic organ that could simulate the sounds of the oud, qanun, and nay, among other instruments.

The electronic keyboard became popular as a substitute for classical instruments or an addition to them in the 1990s. The wide use of electronic sounds simulating classical instruments can be heard in the introduction of Majida El Roumi's 1991 song "Kalimat" (words).

Modern Music Bands in the Arab World

At the beginning of the 21st century, bands and groups emerged that utilized electronic music capabilities to mimic popular Western pop music styles, such as the Kuwaiti band Guitara with their 2001 song "Ya Ghali" (oh precious one).

Around the same period, many DJs began to rework Arab heritage through electronic music rhythms, like DJ Saeed Murad's 2003 album "Alf Leila Wleila" (one thousand and one nights) where he used excerpts from Umm Kulthum's songs as musical interludes for his beats.

Shaabi Music and Music Videos

The electronic keyboard played a significant role in shaping what is known as popular music in the Levant (shaabi music). Folkloric music was reinterpreted and played at parties, weddings, and clubs. The electronic keyboard could simulate the sounds and rhythms of traditional instruments with greater volume capabilities suitable for larger gatherings, as seen in a 2009 concert in the countryside near Homs-Syria.

In the early 21st century, music videos, a new phenomenon in the Arab world, utilized the electronic organ's ability to play simple, stereotypical rhythms and sounds that were easily digestible by the public and produced at a low cost, as in Ehab Tawfik's 2008 song "Ala Kefak" (as you want).

Electronic dance music rhythms also permeated most Arab pop songs, as seen in Carol Samaha's "Sahranin."

More mature experiments handled the classical Arab music heritage reasonably through an alternative electronic music framework, such as Hello Psychaleppo’s 2013 track "Tarab Dub."

Conclusion

Arab music is a dynamic cultural phenomenon, continually influenced by and influencing its environment. Naturally, Arab music has been influenced by the developments in electronic music that entered the scene since the 1970s. This period saw the introduction of electronic instruments like the electric guitar and synthesizer into Arabic songs, thanks to pioneers like Omar Khorshid and Magdi El-Husseini. These instruments helped familiarize the Arab ear with electronic music through well-known classical works.

In the 1990s, the widespread adoption of the electronic keyboard made it a popular substitute for traditional instruments or an addition to them, capable of simulating their sounds and traditional rhythms. This influence continued into the early 21st century, with bands and groups using electronic music to mimic Western styles and experiment by fusing Arab music heritage with electronic music rhythms. The development of recording technologies and computer programs significantly advanced music composition and performance, with the MIDI system enabling computers to communicate with electronic musical instruments, leading many musicians to shift from traditional electronic instruments to computer programs.

However, the adoption of Western electronic music and techniques in Arab music came at a cost. Complex rhythms, improvisation, and maqams with microtones were often excluded due to their difficulty and aesthetic divergence from popular electronic music. Despite this, some composers have skillfully embraced these techniques, demonstrating the ongoing adaptability and innovation of Arab musicians.

Wilson, D. R. (2017). Failed Histories of Electronic Music. Organised Sound, 22(2), 150-160.

Bradley, F. (2015). Halim El Dabh: An Alternative Genealogy of Musique Concrète. Ibraaz Essays, 9(5).

https://thearabweekly.com/western-style-music-bands-losing-popularity-egypt

Farraj, J., & Shumays, S. A. (2019). Inside Arabic Music: Arabic maqam performance and theory in the 20th century. Oxford University Press. Chicago.

Originally published on Jun 22, 2024